Part 6 - Baroque Era - A Revolution in Musical Innovation

🖨️ 6. Music Printing & Public Distribution

Before the Baroque Era, music was largely confined to courts, churches, and manuscripts. With the rise of music printing, particularly engraving, music became accessible to a wider audience.

Estienne Roger in Amsterdam and John Walsh in London helped publish the works of Vivaldi, Corelli, and Handel across Europe.

Printed collections made it easier for teachers, amateurs, and performers to own and study music at home.

This democratisation of music fuelled a culture of independent learning, performance, and publication - a trend that Classical composers would fully embrace.

👥 7. The Rise of the Composer as an Individual

The Baroque Era marked the emergence of the composer as a public figure, rather than merely a court servant:

Handel became a music entrepreneur in London, writing operas and oratorios for public audiences and founding his own production companies.

Vivaldi, though a priest, was a prolific performer and composer whose fame spread internationally.

J.S. Bach synthesised national styles (Italian, French, German) into a spiritual and intellectual musical language that would be revered for centuries.

This rise in artistic identity gave composers the freedom to develop unique voices, a cultural shift that would mature fully in the Classical and Romantic eras.

🌍 8. A Glimpse of Global Influence

While Baroque music was largely Eurocentric, this era saw the first curious and symbolic engagement with global sounds:

Turkish janissary (infantry) percussion influenced operas and marches.

Composers mimicked or referenced Chinese, African, and Indigenous elements - though often from a Euro-imagined lens.

Though limited and often exoticized, these encounters hinted at the early threads of musical globalisation, which would grow stronger in the centuries to come.

✨ Legacy & Transition to the Classical Era

By the time J.S. Bach died in 1750, the Baroque Era had set the musical world ablaze with:

Form and drama (opera, cantata, oratorio)

Clarity through tonality and harmony

Instrumental brilliance (concerto, suite, fugue)

Technical advancements in instrument building and tuning

Public accessibility through printing

Individual voice and entrepreneurship

The Classical Era would refine this energy - bringing balance, elegance, and formal symmetry to the innovations the Baroque had boldly introduced.

The Baroque Era (c. 1600–1750) was a time of explosive growth and change in the world of music. More than just an age of ornate beauty, the Baroque period laid the technical, structural, and expressive foundations that shaped the music of the Classical Era and beyond. While earlier chapters explored sacred and secular forms, instrumental genres, and their role in Baroque society, this concluding chapter focuses on the musical innovations that made the Baroque so revolutionary - and timeless.

🎭 1. Opera: The Birth of Dramatic Music

Although covered in earlier chapters, it’s worth noting that opera was not just an art form - it was a laboratory of innovation in the Baroque that fused music, drama, and stagecraft into one powerful form. Originating in Italy with the Florentine Camerata, opera sought to revive the spirit of ancient Greek tragedy through monody - a single melodic voice supported by harmonic accompaniment.

Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) became one of the earliest masterpieces, blending recitative and aria to convey character and emotion.

Opera moved beyond royal courts and became a public art form, especially in cities like Venice, which opened the first commercial opera house in 1637.

Opera was more than entertainment - it was a musical innovation that prioritised human emotion, narrative, and visual spectacle, and it set the stage for expressive vocal writing across all genres.

🎼 2. The Rise of Tonality

One of the most important developments in the Baroque period was the establishment of tonality - the system of major and minor keys that dominates Western music to this day.

Baroque composers moved away from Renaissance modes and began using functional harmony, where chords like the tonic (I), dominant (V), and subdominant (IV) created clear tension and resolution.

This gave music a sense of direction, enabling composers to create long-form structures like fugues, sonatas, and concertos.

The circle of fifths and modulation (changing from one key to another) became tools for dramatic storytelling in both vocal and instrumental music.

This move toward tonal clarity not only supported the emotional drama of Baroque music - it provided the harmonic blueprint for the Classical Era.

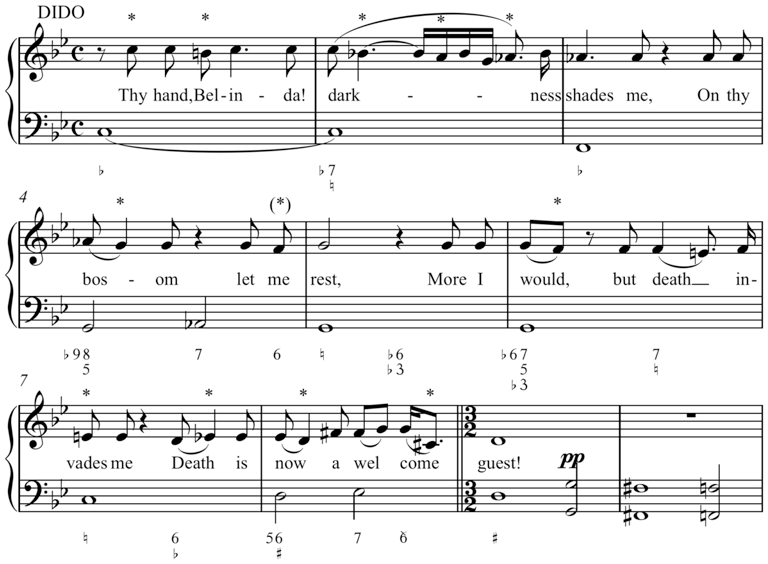

🎹 3. The Basso Continuo & Figured Bass

Baroque music is defined by the basso continuo, or continuous bass line, often played by a keyboard (harpsichord or organ) and a bass instrument (like cello or bassoon). This formed the harmonic foundation of most Baroque compositions.

Figured bass notation allowed performers to improvise chords based on numeric symbols, encouraging flexibility and real-time creativity.

It was used across genres - from operas and cantatas to sonatas and concertos.

The basso continuo not only supported harmony - it also elevated the role of the keyboardist, paving the way for virtuosic solo keyboard works and improvisational playing.

🎵 4. Instrumental Innovations & Orchestration

The Baroque Era witnessed an explosion in instrumental development and ensemble writing:

The violin family reached new heights thanks to master luthiers like Stradivari, Guarneri, and Amati.

Wind instruments (such as the baroque flute, oboe, and bassoon) were refined for better intonation and tonal beauty.

Composers like Corelli, Vivaldi, and Telemann explored orchestral textures and began writing for specific instrumental colours.

The Baroque orchestra became a dynamic body, and this intentional orchestration laid the groundwork for the symphonic structures of the Classical Era.

🎹 5. Keyboard Music & Equal Temperament

The Baroque period saw a dramatic expansion in keyboard music and experimentation with tuning systems:

Composers like Bach, Scarlatti, and Couperin wrote preludes, fugues, inventions, and suites that showcased the expressive and technical potential of the harpsichord and organ.

The development of equal temperament allowed keyboards to play in all 24 major and minor keys without sounding out of tune.

Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (Books I & II) became a landmark in this innovation - demonstrating that music could now move freely across keys, a breakthrough that became central to Classical composition.

Melody from the opening of Henry Purcell's "Thy Hand, Belinda", Dido and Aeneas (1689) with figured bass below the bass line.