The Classical era (c. 1750–1820) marked a turning point not just in music, but in the way society approached knowledge, expression, and faith. Guided by Enlightenment ideals - reason, clarity, balance - composers reimagined sacred music for an age that prized elegance over excess and grace over grandeur.

While sacred music remained central to religious life, it evolved into a sound world that emphasised beauty, symmetry, and emotional restraint. Whether echoing through grand cathedrals or refined salons, it aimed not to overwhelm the senses but to uplift the soul with serene reflection and refined devotion.

Where Baroque sacred works stirred the spirit with drama and complexity, Classical composers offered a more intimate, contemplative approach. The result: music that was no less spiritual, but more transparent, poised, and deeply personal.

Song: Gloria in Excelsis Deo (Glory to God in the Highest) from "Mass in B Minor"

Composer: J. S. Bach

Song: Hallelujah Chorus from "Messiah"

Composer: George Frederic Handel

Song: Erbarme dich (Have Mercy, Lord) from St. Matthew Passion

Composer: J. S. Bach

Song: Zion hört die Wächter singen (Zion hears her watchmen's voices) from Cantata BWV 140

Composer: J. S. Bach

Part 2 - Sacred Music in the Age of Enlightenment

Oratorio

The Classical oratorio remained a sacred, narrative work for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, often based on scripture. Though still large-scale, it became more structured, lyrical, and emotionally balanced, reflecting Enlightenment ideals.

Unlike the dramatic contrasts of the Baroque, Classical oratorios favored clarity and flow. Recitatives were shorter and more speech-like:

Secco: Lightly accompanied by continuo (harpsichord + cello); used for quick dialogue or narration.

Accompagnato: Supported by full orchestra; used for dramatic or emotional moments.

Arias became simpler and more melodic, with less ornamentation and clear formal structures - typically ternary (ABA) or rounded binary (ABA′).

The chorus played a central role, featuring SATB textures, homo-rhythmic writing, and graceful harmonies, with light counterpoint for contrast. The orchestra, akin to a Classical symphony ensemble, enhanced mood and character subtly without overshadowing the voices.

Harmony remained within functional tonality, using modulation and secondary dominants to build narrative tension. The overall style prioritized text clarity, dramatic continuity, and refined expression.

Now heard in concert halls rather than churches, Classical oratorios marked a shift from liturgical function to public art, blending faith, reason, and aesthetic beauty. Works like Haydn’s The Creation exemplify this sacred yet sophisticated approach.

Cantata

Sacred cantatas, especially in Lutheran Germany, were essentially mini-oratorios written for weekly church services. These works often included biblical texts set to music, alternating between reflective recitatives, expressive arias, and lively instrumental passages. They typically concluded with a four-part chorale, allowing the congregation to participate in the final hymn. J.S. Bach wrote over 200 sacred cantatas, many of which were performed weekly.

Passion

A Passion is a sacred oratorio that recounts the suffering and crucifixion of Christ, typically drawn from one of the four Gospels. These works combined intense emotional storytelling with intricate musical design, including poignant arias, dramatic choruses (large ensemble sections sung by a choir), chorales ( hymn-like songs with simple harmonies), and narrated recitatives sung by the Evangelist (a tenor soloist who acts as the storyteller, narrating the Gospel text). The result was a deeply spiritual and theatrical musical experience.

Chorale

Central to Lutheran worship, the chorale was a four-part harmonised hymn sung by the congregation. These melodies were simple and tuneful, often carried in the soprano line, supported by rich chordal harmonies in a homophonic texture. The chorale not only anchored church music but also appeared frequently in Bach’s cantatas and Passions as moments of communal reflection.

Song: Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring

Composer: J. S. Bach

Anthem

In the Anglican tradition (Church of England), the anthem was the English counterpart to the Catholic motet. During the Baroque era, anthems grew more expressive, often featuring solo vocal passages, instrumental accompaniment, and bold, full-voiced choral sections. These elements brought a new dramatic flair to English sacred music.

Song: No. II from "O Sing unto the Lord", Z.44

Composer: Henry Purcell

🎼 Sacred Forms of the Classical Era

Many sacred forms inherited from the Baroque era endured - but were transformed by Classical aesthetics. Let’s explore how these forms adapted to reflect the age’s love for balance, clarity, and human-centred expression.

Mass

The Mass remained the most important sacred musical form during the Classical era, preserving its traditional five-part structure: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus & Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. While the format stayed consistent, the musical style evolved to reflect the Classical ideals of balance, clarity, and lyrical beauty.

In contrast to the Baroque Mass, which often featured complex counterpoint, dramatic fugues, and ornate vocal lines, the Classical Mass favoured homophonic textures, clear melodic phrasing, and a more transparent approach to text setting. Melodies were smoother and more symmetrical, typically shaped in 4- or 8-bar phrases with stepwise motion. Harmony was rooted in diatonic tonality, with occasional modulations and secondary dominants for color. Full Classical orchestration - featuring strings, oboes, horns, and later clarinets - was integrated more evenly with the vocal parts, creating a unified and graceful sound.

Instead of layering voices in complex interplay, Classical composers allowed soprano and tenor lines to carry lyrical themes while bass parts provided harmonic grounding. The overall effect was more reverent and accessible, aligning with Enlightenment values and making the sacred text more intelligible and emotionally resonant.

Composers like Mozart and Haydn elevated the Mass to both a spiritual and artistic height, blending ceremonial grandeur with the stylistic elegance of the Classical age.

Influential Sacred Music Figures

Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685 - 1750)

German composer J. S. Bach was a towering figure in Baroque music, known for his deeply expressive sacred works and groundbreaking keyboard compositions. His cantatas, Passions, and the Mass in B Minor reflect profound faith and intricate musical architecture, while pieces like The Well-Tempered Clavier and the Goldberg Variations revolutionized how musicians approached harmony and keyboard technique. So committed to learning, Bach once walked over 250 miles just to hear his musical idol Buxtehude perform.

George Frideric Handel

(1685 - 1759)

Born in Germany and later settled in England, Handel brought sacred drama to the concert stage with his grand oratorios. His most famous work, Messiah, blends biblical storytelling with theatrical flair, making sacred music accessible and emotionally powerful. Legend has it that he was so moved while composing the "Hallelujah Chorus" that he burst into tears - and completed the entire oratorio in just 24 days.

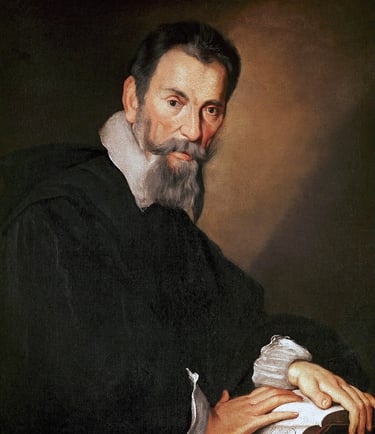

Claudio Monteverdi

(1567–1643)

Italian composer Monteverdi played a key role in transitioning music from the Renaissance to the Baroque. By combining intricate Renaissance polyphony with emotional intensity, he helped usher in a new era of expression. His Vespers of 1610 remains a landmark in sacred music. Monteverdi described his bold new style as seconda pratica, or “second practice,” emphasising the meaning and emotion of the text over rigid musical rules.

Dieterich Buxtehude

(c. 1637–1707)

Danish-German composer Buxtehude was a master of organ music and sacred vocal works. His Abendmusiken (evening concerts) were grand spiritual events that showcased his imaginative harmonies and expressive style. His influence was so strong that the young Bach extended a short trip into several months just to study with him - proving Buxtehude’s importance in shaping the next generation of composers.

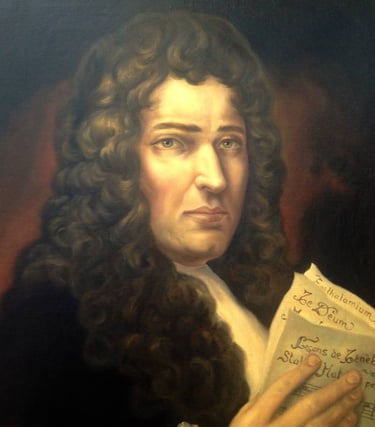

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

(1643–1704)

Charpentier, a French Baroque composer, enriched Catholic sacred music with refined beauty and solemn grandeur. He masterfully combined the graceful elegance of French music with expressive Italian harmonies in his motets, masses, and the famous Te Deum. The majestic prelude of this piece later became the official theme music of the popular 'Eurovision Song Contest'.

Heinrich Schütz

(1585–1672)

Schütz was a pioneer of sacred music in the early Baroque period. Drawing from his studies with Monteverdi in Venice, he brought dramatic intensity and expressive Italian styles into German choral traditions. His Passions, psalm settings, and sacred concertos laid the groundwork for later composers like Bach, bridging the spiritual depth of Renaissance music with the emotion of the Baroque.

The Baroque era transformed sacred music into a deeply expressive and richly textured art form. Composers harnessed new musical tools - like basso continuo, dramatic contrasts, and soloistic writing - to craft works that were emotionally powerful and structurally sophisticated. This was a time when music evolved from the balanced polyphony of the Renaissance into something more dramatic, direct, and personal. Sacred genres like the Mass, cantata, oratorio, and Passion became creative playgrounds for composers to explore harmony, texture, and form. The result was music that could move audiences both spiritually and emotionally - whether performed in a grand cathedral or a concert hall. More than just liturgical function, Baroque sacred music became a platform for innovation. Baroque composers reimagined sacred music as a canvas for bold expression and artistic brilliance. With vivid contrasts, flowing melodies, and richly layered textures, they turned traditional forms into powerful musical experiences. The legacy of composers like Bach, Handel, Monteverdi, and their contemporaries didn’t just serve rituals - they shaped the sound of an era and laid the groundwork for everything that followed.