While sacred music dominated much of the Renaissance period, composers also turned their attention to the world beyond the cathedral. Secular music - written for courts, festivities, private homes, and theatres - reflected the human experience in all its diversity: love, nature, celebration, and sorrow. Unlike sacred music, which was typically sung in Latin, secular pieces were performed in the vernacular - the everyday languages of Italy, France, Spain, and England - making them more relatable and widely enjoyed. In this chapter, we explore the most influential forms of secular music during the Renaissance and the composers who brought them to life, paving the way for the expressive developments of the Baroque era.

Madrigal

The madrigal was one of the most popular secular vocal forms of the Renaissance. Typically written for several voices and sung without instrumental accompaniment, madrigals set poetic texts - often about love, nature, or mythological themes - to expressive music. Early madrigals were relatively straightforward, but later examples became highly sophisticated, employing techniques like word painting, where the music directly mirrors the meaning of the lyrics (for example, using ascending scales to depict 'rising sun' or 'joy'). Italy and England became major centres for madrigal composition.

Song: Cruda Amarilli (Cruel Amarilli)

Composer: Claudio Monteverdi

Song: Tant que vivray (As Long As I Live)

Composer: Claudin de Sermisy

Song: El Grillo (The Cricket)

Composer: Josquin des Prez

Song: Ríu Ríu Chíu (A Bird's Call - onomatopoeic)

Composer: Anonymous

Part 3 - Secular Music of The Renaissance

Chanson

The chanson was the French counterpart to the madrigal, typically written for three or four voices. These songs were elegant and lively, featuring lyrical melodies and clear rhythmic structure. Like madrigals, chansons used word painting and vivid text settings but were generally lighter in tone. Although originally composed for voices alone, it was common practice for instruments such as lutes, viols, or recorders to accompany or double the vocal parts, especially in informal or secular performances.

Villancico

In Spain, the villancico emerged as a popular form that could be either secular or sacred. Characterised by a simple, strophic structure and often dance-like rhythms, the villancico was accessible to a wide range of audiences. It typically featured a refrain (i.e., a repeated line or set of lines in a song, typically at the end of each verse), with alternating verses and choruses, and its melodies were catchy and memorable.

Frottola

The frottola was an Italian song form that preceded the madrigal and laid its foundations. Typically written for four voices, the frottola was mostly homophonic, with a clear melody in the upper voice and simple chordal accompaniment from the lower voices. This made it much easier to sing and understand than the complex polyphony of earlier music. Their texts were often humorous or playful and these pieces were frequently accompanied by instruments and enjoyed great popularity in the early 16th century.

Balletto

A balletto is a vocal composition designed to imitate the character of dance music. Balletti were cheerful, rhythmically regular pieces, known for including nonsense syllables such as “fa-la-la” in the refrains. Their structure was simple and their appeal immediate, making them popular across Italy and England.

Song: Now Is the Month of Maying (i.e May is the month for festivities)

Composer: Thomas Morley

Consort Song

A consort song was an English Renaissance form featuring a solo voice accompanied by a group of viols (string instruments). Unlike madrigals, which used multiple voices, consort songs highlighted a single melodic line with rich instrumental support. They often set serious or lyrical poetry in English.

Song: Lullaby, my sweet little baby

Composer: William Byrd

Key Terms to Remember:

Word-painting : A technique where the music reflects the literal meaning of the lyrics (e.g., ascending notes on the word “rise”).

Doubling: When an instrument or voice plays or sings the same part as another voice or instrument, often to reinforce the line.

Refrain: A recurring line or group of lines, usually with the same music and text, that returns throughout a song.

Verse: A section of a song with changing text but usually repeated music, telling the story or developing the theme.

Chorus: A repeated section with the same music and text each time, often the most memorable and emotionally expressive part of the song.

Strophic: A song structure where the same music is repeated for each stanza (verse) of the lyrics.

Homophonic: A texture where all voices move together rhythmically, often with one clear melody and chordal accompaniment.

Polyphonic: A texture with two or more independent melodic lines performed at the same time.

Influential Secular Music Figures

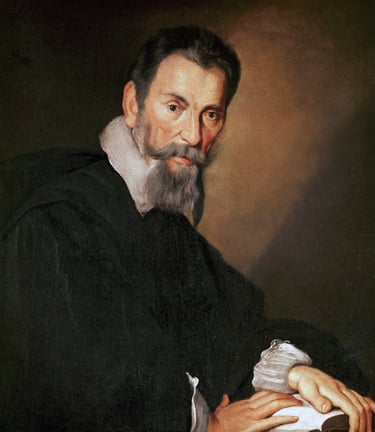

Claudio Monteverdi

(1567 - 1643)

A pivotal figure in the late Renaissance and early Baroque era, Monteverdi is renowned for his madrigals to which he brought emotional depth and dramatic contrast. He is also credited with composing one of the earliest operas, L’Orfeo, which helped usher in a new era of theatrical and expressive music.

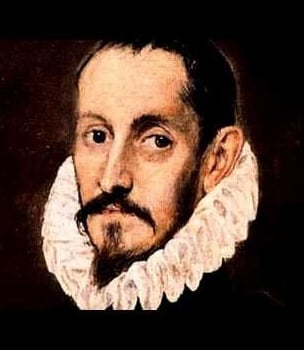

Carlo Gesualdo

(c. 1566–1613)

Gesualdo is an Italian nobleman and composer known for his intensely expressive and harmonically adventurous madrigals. His use of chromaticism and unexpected harmonic shifts was highly unusual for his time and continues to intrigue musicians and scholars today. Gesualdo's music is deeply personal, and his dramatic life - including his notorious murder of his wife and her lover - has further fuelled interest in his work.

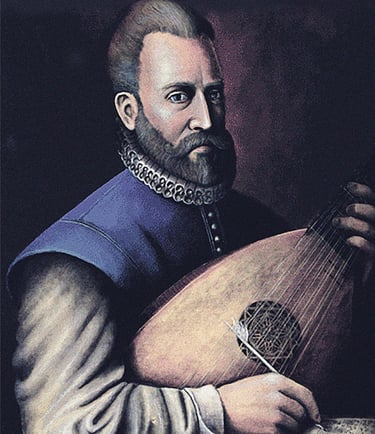

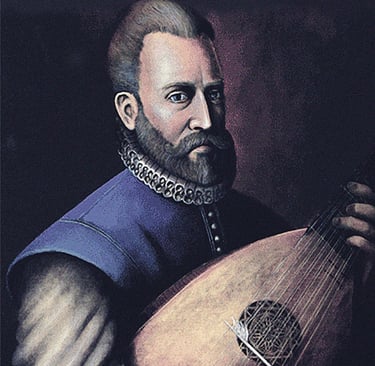

John Dowland

(1563–1626)

An English lutenist and composer, his melancholic songs reflect the introspective spirit of the English Renaissance. His best-known piece, Flow My Tears, remains a defining example of Renaissance lute song. Dowland typically wrote for solo voice and lute, combining poetic texts with subtle musical expression.

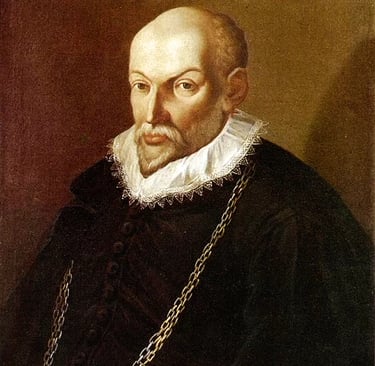

Orlando di Lasso

(1532–1594)

Orlando di Lasso was a prolific Franco-Flemish composer known for his versatility and international acclaim. Working across Europe and serving as court composer in Munich, he wrote over 2,000 works in various languages and styles, including sacred masses, motets, madrigals, chansons, and German lieder.

Michael Praetorius

(1571–1621)

A German composer and theorist best known for his contributions to early instrumental and dance music. His collection Terpsichore contains over 300 instrumental dances and remains an important source for understanding Renaissance instrumental practices.

Diego Ortiz

(c. 1510–1570)

A Spanish composer and music theorist whose treatise Trattado de Glosas explored improvisation and ornamentation in instrumental music. This work is considered one of the earliest systematic approaches to instrumental variation and demonstrates the growing importance of instrumental music during the Renaissance.

Secular music in the Renaissance period played a crucial role in shaping the direction of Western music. Through the development of expressive vocal forms like the madrigal and chanson, and through innovations in instrumental music, composers of the Renaissance laid the groundwork for the emotional and dramatic intensity of the Baroque period. Their contributions not only expanded musical language but also brought music closer to the everyday lives and languages of people across Europe.